Gojek is an Asian super app based in Jakarta that does everything from motorcycle ride-hailing to bill payments. The startup has become Indonesia's biggest success story. And after its merger with homegrown e-commerce giant Tokopedia, it's rumored to be valued at over $28.5 billion. Major investors include Tencent, Google, Sequoia, Visa, Temasek, and a host of other big guys.

Social enterprise

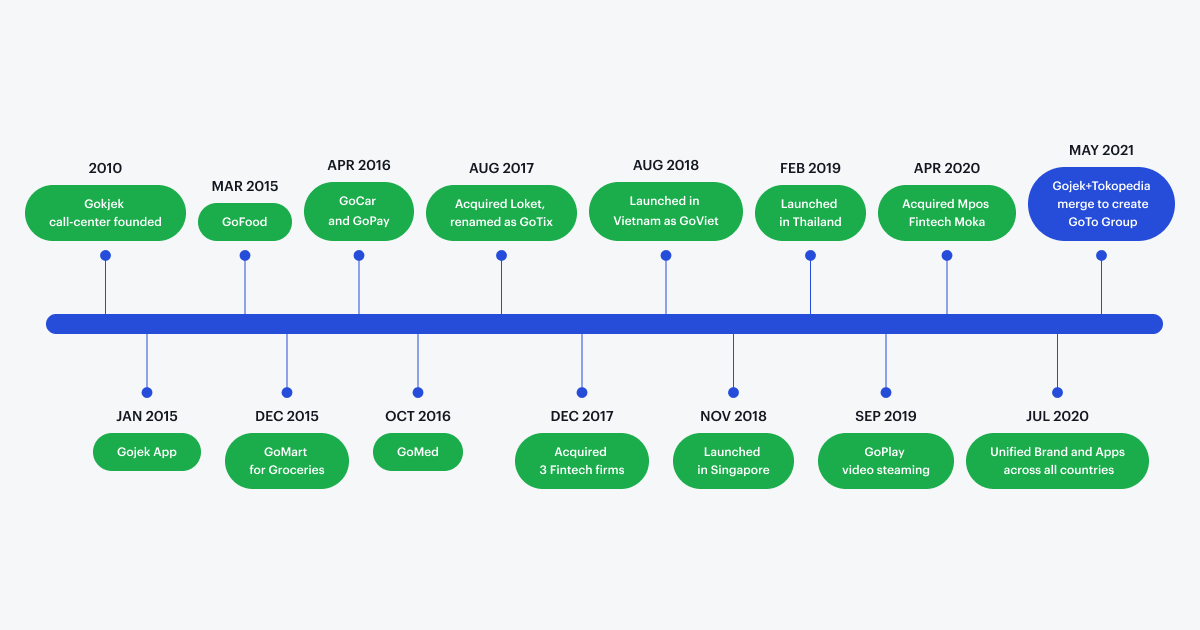

But while Gojek stands as an industry giant today, its origins were modest. For Gojek, its journey has been quite a ride. Literally! In fact, for five years of its existence, Gojek was basically a low-tech social impact company operating a call center for motorcycle taxis. In the words of the founder, Nadiem Makarim, Gojek was conceived as a “social enterprise” that is focused on “increasing driver income”.

Nadiem founded the company in 2010 after noticing inefficiencies in the informal ride-hailing sector in his native Jakarta, a city notorious for its awful traffic jams. After returning from his MBA at Harvard, he discovered the potential of applying newly developed business models from Silicon Valley to solve entrenched problems in Indonesia. Addressing Jakarta's endless “macet”, or traffic, was certainly a worthy endeavor: a real-life problem that can be solved only with determined execution.

Uber for the tropics, anyone?

Besides, helping underemployed motorcycle drivers—Ojeks—make a decent living by better matching supply and demand was a worthy social impact goal for a socially conscious young entrepreneur like Nadiem. However, the project never really got the traction that Nadiem and his team were expecting. Gojek was launched with 20 drivers and a call center, and it languished for four years, while its founder worked at Rocket Internet and other local digital ventures.

Gojek, meanwhile, hadn't quite become a Rocket.

Getting out of the building

Nadiem had the right instinct to frequently interact with ojek drivers, mostly, young and middle-aged men, who spent most of their time lounging around outside shopping malls, offices, and other crowded places, smoking kretek—Indonesian clove cigarettes that envelop the air with their sweet aroma—and waiting on their motorcycle for a customer to approach them. While on a trip from South Jakarta, he found that drivers not only had to haggle prices for each trip, they could not pick up new customers in the city center, because the mafias that controlled them had their territories fenced off.

You bet Nadiem got out of the building and did his customer discovery homework. Steve Blank would be proud!

Knowing their buyer persona well, Nadiem had outfitted Gojek drivers with their iconic green jackets, as well as helmets with the original Gojek logo. A more professional outlook would help attract more clients, he thought. All this was well and good, but Gojek was still an offline social enterprise. No tech, no app. In fact, they won the 1st prize they received in Bali from the Global Entrepreneur Program Indonesia… in the non-tech category. In the words of Eric Smith, former CEO of Google, "Gojek has been about scheduling and organizing what has been an informal service economy".

Persistence

The lack of scale made Nadiem hesitant about leaving his full-time job in order to devote himself fully to Gojek. However, success in the startup world often comes to those who persist. Founders who are gritty and tenacious, often stick around for long enough and end up being well placed with the big wave comes. You just need to wait for four years without throwing the towel. So in 2014, with Uber planning to enter South East Asia and Gojek's local rival Grab entering the scene, investors started taking a second look at Gojek's potential.

It was time for Nadiem to ride the biggest wave of his life.

Fortune favors the bold. And Nadiem dared to get lucky. Seizing the opportunity, he raised a seed round from NSI, now called OpenSpace ventures. He also reshuffled his co-founding team, bringing Kevin Aluwi from Rocket Internet as his CFO. He joined Nadiem's schoolmate Michaelangelo Moran to power up the founding team. With money in the bank and wind behind his sails, he set off to build Gojek's mobile app. It became an instant hit, with orders skyrocketing from 3,000 to 100,000 a day.

Finally, Gojek became a rocket. Raising Series A was a piece of cake, and investors wanted more. By 2016, Gojek had become Indonesia's first unicorn.

Bundling

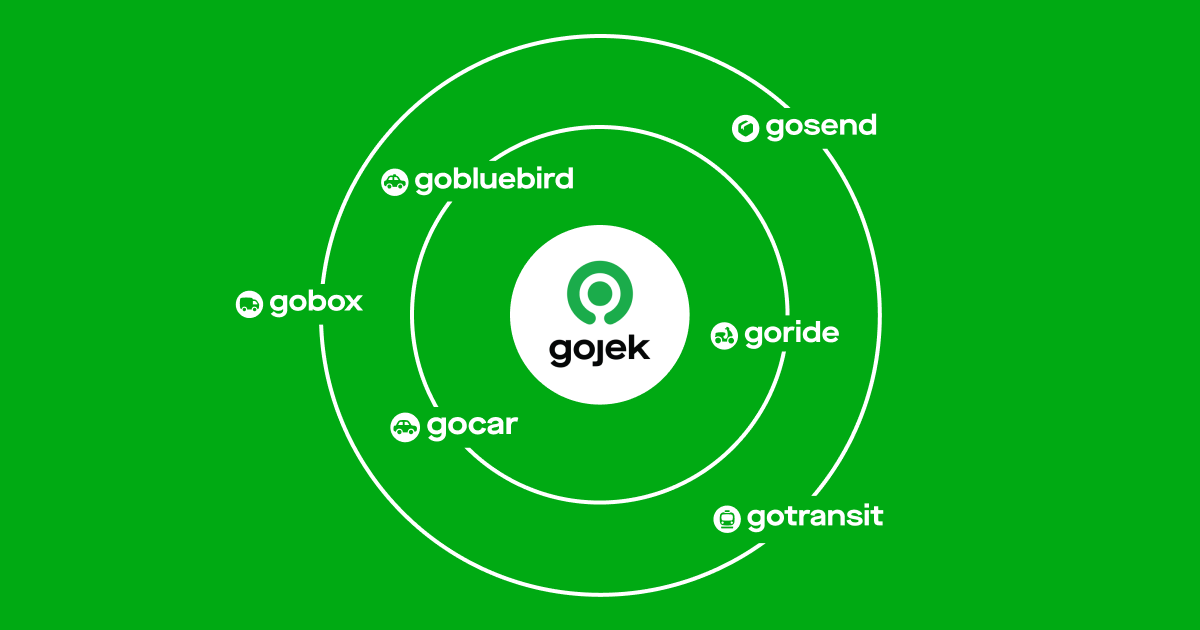

Silicon Valley product purists may find it heretic, but Gojek's digital product play was about bundling a bunch of different services on top of a last-mile delivery network. Forget about an app for this and an app for that. So from being an offline zombie, Gojek went all the way to the other extreme. It became a super app, powered by an army of tech engineers it could now afford to pay. With millions of Jakartans using the app for ride-hailing, adding food delivery, bill payments and other services was a no-brainer.

When you think about it, startups at their core are about solving people's problems. Gojek realized that since the Indonesian ecosystem was in its infancy, they were in a unique position to solve a host of everyday problems for their users. And cross-selling a new service to an existing user had a CAC of zero, while it helped increase the company's LTV. No wonder investors were queueing up for the chance of investing.

But getting there was anything but easy. Nadiem had all the attributes an investor could look for in a founder: Harvard MBA, ex-McKinsey, ex-Rocket founder, and to top it all he was selected as a Global Shaper by the World Economic Forum. Even then, it took him years until he secured the necessary funding. You may think, “Aha, Indonesia doesn't have wealthy investors”. Think again. Indonesia had investors aplenty. But in the early 2010s, most of the money was channeled to the natural resources sector. There were hardly any Indonesian homegrown tech success stories, and anyway it was almost impossible to find good developers in Jakarta.

In 2012 if you had a coal mine on the island of Borneo, you would surely get financing. But raising a round for a social startup was almost impossible. What's more, while Nadiem and his Gojek team struggled, one of his Harvard classmates, Malaysian-born Anthony Tan, was building a rival giant: Grab.

Regional rivals

Both decided to start a mobility startup based on Uber's model. In fact, both had the idea during their MBA. But Anthony was luckier when it came to funding. He found ready backers among family and friends. And back in Singapore, Southeast Asia's financial center, he didn't have to compete against palm oil plantations and zinc mines for investors' dollars.

The die was cast for both entrepreneurs, friends, and rivals. Anthony was clear from the beginning that he was going to create a regional company and that included Indonesia. Things heated up when in 2014 SoftBank decided to invest a Gazillion dollars in Grab. And Grab was as determined as Gojek in becoming Southeast Asia's leading super app.

Super apps like Gojek or Grab may be a uniquely Asian phenomenon. They may thrive in emerging markets elsewhere too. Whatever their origin, synergies between adjacent service sectors are their raison d'etre. In Gojek's case, the clearest relationship is between the motorcycle taxi service with food delivery, and between the mobility service and micropayments.

GoFood and GoPay were born in 2016, and they remain two of Gojek's most powerful verticals. GoPay, together with its rival Ovo is competing in the B2C micropayments market in Indonesia. Today they control over 50% of the sector. Guess who controls Ovo? That’s right: Grab and SoftBank, Gojek's eternal rivals.

Global model

Gojek's story has come to inspire entrepreneurs in other corners of the planet, as has Grab. Rappi in Colombia is a kind Latin American Grab. And entrepreneurs in Africa are actively looking at Gojek. Gozem, founded by two Frenchmen specifically got inspiration from Gojek, and aims to replicate the super app concept for the West African region.

In mature markets "unbundling" — or the specialization of apps by specific verticals - has been the norm in the last decade or more. But not so in emerging markets. Once you have almost millions of users on your platform, the marginal of cross-selling related vertical services is zero. It's no wonder that in Indonesia, the main source of inspiration for startups like Gojek is not Silicon Valley, but China.

Apps like WeChat, AliPay, Meituan Dianping have features that are much more similar to Southeast Asian super apps than Silicon Valley startups. It also explains Tencent, WeChat's parent company's interest in Gojek, and why it invested a few spare hundreds of millions of dollars.

Nadiem left the company in 2019 and today serves as Indonesia's Education Minister. He's still faithful to the idea of making real-life changes to his country and improving the situation of his fellow citizens. We can only wish him every success.

With its merger with Tokopedia, the Gojek saga continues.

Terima Kasih!